Yesterday Historic Boulder, our local non-profit preservation advocate organization, announced that it has purchased the long-unoccupied Hannah Barker house. Most folks here in Boulder know it better as that dilapidated, boarded up white elephant on Arapahoe west of 9th Street. Buying the house themselves certainly is a bold put-your-money-where-your-mouth-is move. And it is not the first time.

today

Historic Boulder largely got its start in an effort in the early 1970's to save the threatened Boulder Theatre. Rather than just picket the building and shout at some public hearings, they bought the building and secured it for a few years until a buyer could be found. They have done similar purchase-to-perserve efforts since including the Highland Lawn School which has become the Highland City Club building.

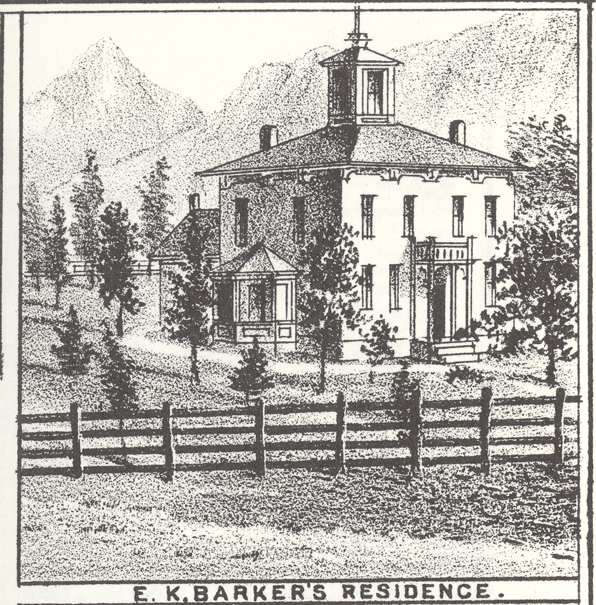

1880 drawing

Sitting on the Landmarks Board, I hear a lot of complaining about the entire preservation process. Maybe more than most places, in the West there is a strong owner's rights ethic that often runs smack into perservation efforts which attempts to protect our cultural heritage by primarily regulatory means. The recent success of Historic Boulder purchasing the Barker house mutes that conflict and lends immense credibility to the organization and the act of preservation in general. And in the end, Historic Boulder will take the risk and the community will gain the benefit of a truly architecturally and historically significant building saved.

One of the most interesting aspects of this project will be Historic Boulder's intention to use the renovation of the house as a model for demonstrating that preservation, old houses and sustainability concerns can all work seamlessly together. In Boulder we have a wealth of talented and experienced architects, builders, energy consultants and building science professionals that can be brought to bear on this project.

The building is currently a much-abused shell, but even in that state it has a tremendous amount of embodied energy that needs to be accounted for. Embodied energy is the all the energy inputs that the existing building represents - the energy required to lay the masonry, frame the house, and it also includes the trapped energy that was used in the creation of all those bricks and all that lumber, including its transportation.

Most energy conservation ordinances and programs do not give sufficient credit for embodied energy and rely more heavily on building systems and performance to meet sustainability goals. Embodied energy is difficult to calculate, but only by carefully stepping through this process can we have a quantitative marker that proves "the greenest building is the one already there."

circa 1885

Hopefully a careful and exhaustively documented renovation process can convince the City of Boulder and other municipalities that they must included embodied energy as an integral part of their sustainability regulations and give it it's proper credit. At that point, perservation and sustainability can be partners, not often contentious constituents.

Congratulations to Historic Boulder and all its volunteer members who made this possible, as well as the City of Boulder preservation and planning staff that aided in this much-needed process.

(All image from Historic Boulder and/or The Boulder Public Library, Carnegie Branch for Local History)